BlackCAT

My work in astronomy is largely concentrated in the work I do for the High Energy Astrophysics Detector and Instrumentation (HEADI) Lab, where I focus mostly on the BlackCAT CubeSat mission. This mission involves a wide-field X-ray imaging telescope placed on a 6U CubeSat satellite to observe gamma-ray bursts and other high-energy transient and flaring sources using novel X-ray hybrid CMOS detectors. My most notable contributions to the mission have been the assembly of the payload that will soon be integrated into the CubeSat system, the design and construction of various components of the setup used to calibrate the detectors, and, more recently, programming a package to enhance detector imaging capabilities using regularized maximum likelihoods.

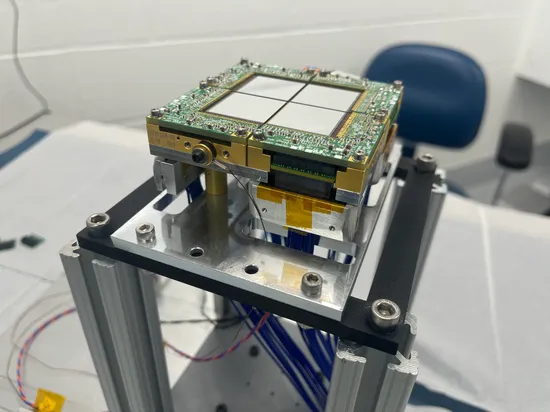

Working part-time in the lab, I have contributed to a wide range of projects, including 3D printing, epoxy work, and machining. I have designed, constructed, and leak-checked various additions to many of the vacuum systems used in the lab. Recently, as the calibration of BlackCAT was in full swing, I spent dozens of hours collecting data for both detector imaging and thermal calibration. My standout experience in the lab has been the final construction of the payload, which included the novel X-ray Hybrid CMOS detectors (seen below), the detector module, the circuitry that keeps everything running, and the cabling that makes everything possible. Before the systems engineer and I assembled the payload one final time and epoxied down every single screw, we had already spent many hours in the clean room assembling and disassembling the detector module, giving us the expertise to get it right for the final attempt.

A lot of my early work in the lab focused on the design and manufacturing of the system used to control detector temperatures during the calibration of BlackCAT. I designed and made various thermal pieces that allow liquid nitrogen to cool down the detectors while also heating them using heaters epoxied into thermal blocks. Having both a source of cooling and tunable heating allows a LabVIEW program to keep the temperatures of the detectors quite constant, even at temperatures as low as 220K. I became particularly skilled at constructing thermal straps, which are layered sheets of copper strips that clamp between thermal cooling blocks on both ends. These straps allow heat to travel between the various components of the calibration setup we used.

Now, as the in-lab work related to BlackCAT slows down due to the mission hitting the final phase of payload integration and testing prior to launch preparations, I am working on an exciting project focused on enhancing detector image quality. A powerful approach used in radio astronomy to resolve images, popularly employed by the EHT collaboration to capture an image of M87, involves synthesizing images using regularized maximum likelihoods (RML). The detectors can only do their best when taking images of the sky; nevertheless, a true image of the sky does theoretically exist. Enhancing the images from the detectors to something closer to a true image of the sky is where RML becomes highly valuable. In our approach, we are maximizing the probability that an image we synthesize—using a chi-squared distribution and tuned regularizer functions—matches what we would theoretically expect X-ray events to look like. A large portion of the heavy-lifting in the code is handled using PyTorch, a machine learning library. We employ algorithms such as gradient descent and ADAM to manage the maximization process while incorporating regularization.